Ever since I was young, I knew I wanted to have children — a large brood of little ones, with all the squabbles and exhaustion and love that brings. When I started dating my now-wife, Anya, in 2004, we knew we were too old — I was 32, she was 33 — to waste time on a relationship where the other wanted a completely different life.

So we talked early on about the important stuff, and I told her I could happily compromise on everything else but I needed to have children. Then, when we started talking about getting married, she sat me down for a chat.

‘Look,’ she said, ‘I don’t want to put pressure on you, but biology means it’s going to get harder for me. I don’t want to end up on the other side of 40 and you say, “Let’s have kids”, and then I can’t get pregnant and we end up splitting up because of it.’

But I just didn’t take it in.

Anya and I worked together on my BBC travel documentaries, she filming and researching behind the scenes, while I was front of camera. We were travelling the world for up to six months a year.

I always thought the babies would come, but at an appropriate moment. They would be slotted into a schedule. Our schedule. Nature would play ball and fall in with our plans. How wrong I was. In the summer of 2008, after marrying the year before, we began trying for a child. For many months, we tried everything from hypnotherapy to having sex upside down.

Ever since I was young, I knew I wanted to have children — a large brood of little ones, with all the squabbles and exhaustion and love that brings

We even timed lovemaking to coincide with changes in Anya’s body temperature (women’s fertility starts to peak two or three days before ovulation, signposted by a slight change in body temperature), which is not an easy task when you’re on the road filming. It meant being intimate whenever and wherever we were, be it on a ferry, on an abandoned film set or up a mountain.

Eventually, after a year-and-a-half of trying [by then aged 37 and 38 respectively], we sought advice from pricey fertility experts. When Anya’s test results came back all clear, the spotlight turned on me.

I saw a male fertility specialist and filled in long documents detailing my lifestyle and my nutritional intake, or the lack thereof, before giving a sperm sample for testing.

Then I found myself sitting in a private fertility clinic in London, where I heard the worst news I could have imagined.

The fertility specialist bustled in and sat down with my notes. She had a cool manner, like a headmistress, but perhaps she was just unwilling to comfort me with inappropriate warmth.

‘I’ve got your test results,’ she said, ‘and I think you should prepare yourself for some bad news. I won’t make any bones about it,’ she tapped the papers. ‘I’m very sorry to have to tell you, but you are basically infertile.’

I would not be able to have children. It was the starkest of messages: I could hardly take it in.

She told me I had loads of sperm but their morphology was terrible. We’d never heard the term before.

When I started dating my now-wife, Anya, in 2004, we knew we were too old — I was 32, she was 33 — to waste time on a relationship where the other wanted a completely different life

‘Your sperm are deformed,’ said the headmistress, looking over her glasses at me. ‘They will never be able to break into Anya’s eggs.’

She started listing different figures from my sperm test. I had 0 per cent normal sperm. Zero. Nothing. They had also checked sperm motility. My sperm were swimming around in circles, or moving energetically without going anywhere. Ironically enough, considering my day job, they were not good travellers.

‘But surely,’ Anya said, ‘there’s something we could do? He works all hours, eats fairly badly, doesn’t get enough sleep. He could have earlier nights, live more healthily.’

The headmistress shook her head. ‘I’m sorry, but no,’ she said. ‘I don’t want to give you unrealistic levels of hope.’ She was adamant that morphology is one of the hardest things to improve. I was quickly lost to my fears and remember swaying in my seat. It felt I had been deprived at a stroke of my very reason for being.

I’d already had an awareness of what it would mean to miss out on having my own family, and had told Anya that unless I could have children I was very likely to go mad. I didn’t think I would be able to cope with life if I couldn’t become a father.

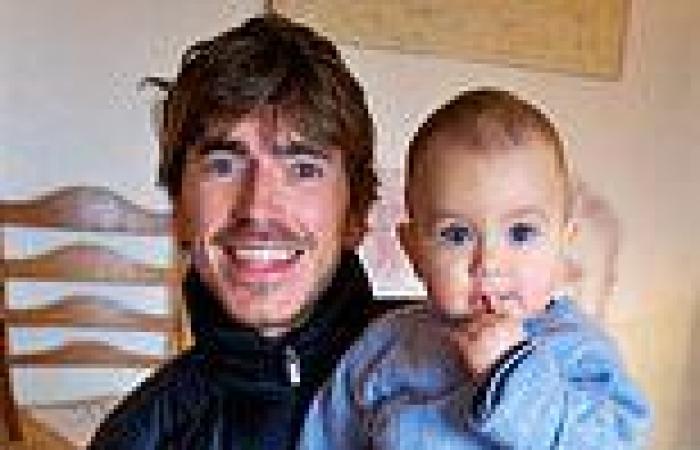

But there seemed to be no way around the specialist’s verdict. Natural conception was impossible. I was told there was no chance that I could have my own baby. My sperm were not viable. They were bloody useless. Yet despite this doomsday prediction, today Anya and I have a son, Jake, who’s now aged ten. He is the centre of our world, beloved beyond all measure.

How did this happen? Well, despite what the specialist told us, I was able to transform my fertility through sensible, practical measures, along the lines that Anya had suggested.

I overhauled my unhealthy diet. I exercised, doing intense British Military Fitness classes run by former Army instructors. I bought new underwear that let everything hang loose, and traded my way-too-tight jeans for combat trousers. I even tried sitting on a rubber ring that was supposed to give my undercarriage some space. Seriously. I wanted to have a child and was happy to do anything.

And it worked. After just a few months following this new regimen, tests showed the headmistress had been wrong. While my results still weren’t amazing, my sperm were completely viable. I had a chance of becoming a father.

I realise this is intimate. I wasn’t sure whether I should write about such a thing, especially as my son will one day read this. But I want to be honest about what we went through because it might help someone else.

Because if you want to have children with a future partner, don’t imagine Mother Nature will be happy to twiddle her thumbs and, when you decide the time is right, dance to your tune.

I had no inkling that there was anything amiss with my fertility. It was only when I started looking at my lifestyle that I realised how much I was doing wrong.

Despite this doomsday prediction, today Anya and I have a son, Jake, who’s now aged ten. He is the centre of our world, beloved beyond all measure

Aside from my age, there were all sorts of things to beat myself up about. Sperm are sensitive and are particularly badly affected by environmental factors such as heat, pollution and chemicals.

The expert had said many men who spend their days sitting at computers or driving taxis or lorries are effectively cooking their sperm.

Had I done the same with my trips to the Tropics and other exotic places for my television documentaries? I kept thinking of the time I had walked into a nuclear waste dump in Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia, wearing a full-face respirator and a biological and chemical warfare suit only a little thicker than a shower curtain.

The sun had roasted me inside the suit to the point where I thought I was going to collapse. I had to sit down, on top of the radioactive nuclear waste dump. Even at the time, I thought the physical proximity of my testicles, my reproductive organs, to the ground was A Very Bad Idea.

Then there were all those journeys where I’d squashed and squeezed myself into tiny vehicles and small planes in tropical corners of the world. I just couldn’t stop thinking that I had boiled or irradiated my own testicles.

It was desperately painful for me to accept that my travelling might have been part of the reason I was going to be unable to have a family, that my journeys made me a prime candidate for infertility all along.

Anya was also deeply upset, of course. But she was a lot calmer than me, and was sceptical about the sheer finality of the verdict. ‘We are not giving up — change is always possible,’ she would say, as I risked sinking into a miasma of depression.

So what was first to change? After that catastrophic verdict from the headmistress, we decided to go to our original fertility specialist, who was sympathetic and calming.

My sperm test results were definitely not good, she agreed. But she did offer a little light, saying that although we would not be able to conceive normally, or even with IVF, there were other options.

Had we thought about a sperm donor? Adoption? Fostering? Or it might be possible to inject my sperm directly into Anya’s eggs in a more complicated form of IVF called ICSI, rather than just