DR CHRIS VAN TULLEKEN: My identical twin is 3 stone heavier because of ultra ... trends now

My twin brother Xand is a perfect genetic copy of me. So I know, because I’ve been tested, that he and I share a gene that predisposes us to putting on weight.

This came as no surprise to me. I love food, and I’m constantly thinking about my next meal.

If you’re as obsessed with food as I am, then — regardless of what you weigh — you probably have these genes, too.

In my own case, I’m just a bit overweight. So you’d expect my genetically identical twin to weigh roughly the same, give or take a few pounds.

A few years ago, though, Xand was nearly 20kg (3 st)heavier than me. This is a huge amount, in fact the biggest weight difference of any pair of UK twins who’ve been studied by scientists.

So how on earth did my brother manage to become clinically obese?

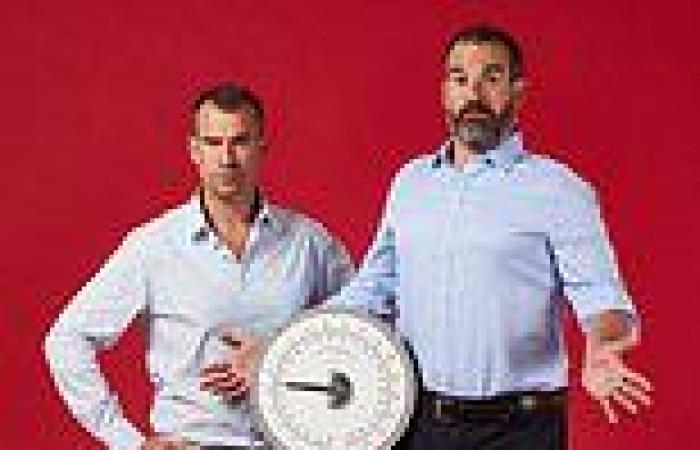

Weighty issue: Dr Chris van Tulleken (left) with his twin brother, Xand

His weight problem began when he won a scholarship to an American university to do a masters degree. Quite suddenly, he was living in the middle of a food swamp.

You may have heard of food deserts —places where shops sell only ultra-processed food (UPF). In the UK, more than three million people don’t have a shop selling raw ingredients within 15 minutes of their homes by public transport. This means it’s difficult to source real food — let alone cook it.

Food swamps are similar to food deserts. Fresh food may be available, but it’s submerged in a swamp of fast-food outlets selling UPF.

And there are plenty of these swamps in the UK. Take Leicester, where a group of teenagers kindly showed me round the place where they all regularly hang out.

At the Clock Tower, a central landmark, they pointed out the shops in the immediate vicinity: McDonald’s, Five Guys, Burger King, KFC, Greggs, Tim Hortons, Taco Bell, another Greggs, Pizza Hut, a chicken shop, Costa, Awesome Chips.

All these outlets sell UPF — edible substances reconstructed from whole food that’s been reduced to its basic molecular constituents. These are then modified and re-assembled into food-like shapes and textures and then heavily salted, sweetened, coloured and flavoured.

Many of the chemicals used have never before been eaten by humans. And evidence is growing that many of them raise our risk of everything from cancer and heart disease to dementia, colitis and diabetes.

So how can you avoid UPF if you’re one of those teenagers in the Leicester swamp? The answer is that it’s all but impossible.

'A few years ago, though, Xand was nearly 20kg (3 st)heavier than me. This is a huge amount, in fact the biggest weight difference of any pair of UK twins who’ve been studied by scientists'

It’s not just the density of fast-food UPF outlets that matter, it’s also the marketing. The teenagers showed me their bus tickets, which are also vouchers for McDonald’s. They also let me look at their social-media feeds, which are crammed with ads for UPF brands.

So are the online games they play. Even the songs they listen to on Spotify are interspersed with ads, largely for fast-food chains. The UPF industry, I realised, has an iron grip on their lives, to the point where McDonald’s has become their de facto community hub.

As one put it: ‘It’s where we hang out, because all the youth clubs have shut down.’

Like the kids in Leicester, Christina Adane — a young food activist from London who was behind the UK petition for free school meals — is aware of how much influence the food industry has over her and her friends.

‘It is scary how successful junk-food companies have been in infiltrating youth culture. Celebrities go on chicken-shop dates to promote new albums, energy drinks are advertised at every event celebrating up-and-coming young artists,’ she told me. ‘Not enough of us realise that these fast-food companies are not our friends. We’re living in a world where one in three children by the age of 11 is at risk of diet-related disease. One in three!’

Needless to say, my brother Xand had no idea that what he was eating might be harmful.

Living in the U.S., he’d found himself surrounded by far more UPF than he’d ever encountered in the UK. Soon, it made up the majority of his diet.

He was also stressed and far from home. And stress has a dramatic impact on the hormones that regulate appetite, increasing the drive to eat more.

What is it about UPF that makes it seem irresistible? As Xand discovered, it’s available everywhere, cheaper than whole foods, quicker to prepare and so soft that it slips down a treat. But that’s not all; added flavouring also draws us in. I talked about this to Barry Smith, an expert ultra-processor who used to advise food companies.

The UPF industry, he explained, exploits the fact smell influences taste. One of Barry’s favourite sensory tricks involves ice-cream.

‘If you go into the freezer for an ice-cream bar, as you rip open the packet, it won’t smell of anything, because it’s too cold,’ he said. ‘So, lots of companies add a scent in the wrapper’s ribbing.’

This not only starts a craving, but it makes us experience the chocolate more intensely.

This trick is probably OK if it leads to real chocolate. Other tricks, however, are actively misleading — such as delicious smells in products so over-processed that they contain no nutrition at all. You can see why manufacturers go down this route. If you get a whiff of barbecued beef, say, you’re more likely to eat an industrially processed substance that has little relation to the real thing.

Mark Schatzker, who belongs to a nutrition research group at Yale, believes the use of flavourings is one of the main problems with UPF. For humans, he says, the way a food tastes and smells is a signal it contains particular nutrients. When we eat an ultra-processed version of real food, however, we simply aren’t getting what its flavouring promises to deliver.

'It’s not just the density of fast-food UPF outlets that matter, it’s also the marketing'

Bear in mind that there are more than 26,000 chemicals in some whole foods, many of which may be responsible for giving us protection against cancers, heart disease, dementia and early death. But most of these chemicals are stripped out by ultra-processing. The result is lots of