Saturday 13 August 2022 10:16 PM The real cop behind Prime Suspect: Sexist officers couldn't beat hard-as-nails ... trends now

One day in early 1990, I arrived at a stunning home in South-West London to be greeted by a striking, petite woman with a fabulous smile and a cascade of red curly hair, an Irish wolfhound by her side.

'I'm Lynda,' she said. 'Do you like dogs?'

This first meeting with crime author and screenwriter Lynda La Plante came during my first year as a Detective Chief Inspector in the Metropolitan Police – and it changed my life.

Lynda's interest in senior female police officers had been piqued while watching the BBC's Crimewatch UK.

The officers talking about murder cases were, she noticed, invariably men.

She made enquiries at New Scotland Yard and learned that there were only three female DCIs in the entire Met. I was one of them.

At the house, Lynda led me into a large, comfortable sitting room where she handed me a giant glass of wine – and a script with the words Prime Suspect typed across the front page.

As soon as I started reading, I was hooked. But I knew the script could be even more realistic.

I did most of the talking over dinner that night as I filled Lynda in on my experiences as a female detective.

She was visibly shocked as I told her that female police officers were routinely classified as either a 'bike' or a 'dyke', and that my nickname on the Flying Squad was 'The Tart'.

I recounted in detail what female officers had to put up with to survive in the job – including a humiliating initiation by male colleagues.

It was Lynda's surprise that made me realise that the behaviour I had come to accept as normal was not every woman's experience at work.

Over the ensuing months, I relayed everything I thought might be relevant to her TV project: the dynamics of a male-dominated policing culture ridden with bravado and male camaraderie; my experience of feeling like an outsider; my efforts to blend in.

I explained I'd always worn expensive skirt suits for work – never trousers – and a smart 'detective' coat to look the part even if I didn't always feel it.

Helen Mirren (as DCI Jane Tennison), John Benfield (as DSI Michael Kernan) and Craig Fairbrass (as DI Frank Burkin) in Prime Suspect Two TV series

All too often, witnesses or suspects would presume a junior (male) colleague was in charge.

'I don't like being called 'Ma'am',' I told Lynda. 'I find it archaic and a bit stiff. I always tell my junior colleagues, 'Call me Boss or Guv, but don't call me Ma'am. I'm not the bloody Queen.' It usually makes them laugh.'

What I didn't realise is that Lynda was studying me and my tics – my tendency to smoke Silk Cuts intensely, my unconscious habit of running my hand through my short hair.

Over time, Lynda fleshed out DCI Jane Tennison into a fully formed and credible character.

Watching Lynda's drama unfold on screen, shortly before it was broadcast in 1991, I chuckled as the redoubtable Helen Mirren channelled my quips.

'Listen,' Tennison tells a detective constable. 'I like to be called Guvnor or The Boss. I don't like Ma'am – I'm not the bloody Queen – so take your pick…'

My delight at La Plante's brilliance was tempered by nerves. A male actor had shown the script to his police friends, who had declared it 'b******s'.

The fact that a bunch of men were trying to discount my experiences spoke volumes: this was deja vu.

I was a DCI with 20 years of policing experience under my belt, 11 of them spent in the Met.

The attempt to drown out my voice reflected my daily reality, where there was no room for a female perspective.

It certainly unnerved Prime Suspect's producer, Don Leaver, who began to worry that they might have a turkey on their hands.

'Imagine my surprise that male officers don't agree with this,' I said to him.

'It's kind of my point. They haven't got a clue what it's like to be a woman on the job.'

I returned Leaver's gaze for what felt like the longest time.

Finally, he spoke. 'OK, Jackie. I trust your experience. We will go with that.'

Women police officers had been virtually invisible in the TV shows I'd grown up watching in the 1960s.

Yet Dixon Of Dock Green and No Hiding Place had done little to deter my 18-year-old self from my chosen career.

It was the autumn of 1969 when I set out to join Leicestershire Police cadets, although my cup of enthusiasm ran dry when I realised that female cadets – and only female cadets – were expected to stick the kettle on.

One fateful day, I was asked to make a round of drinks for senior officers in a meeting led by Deputy Chief Constable Eric Lacey.

He stirred the sugar in his tea, took a sip then promptly spat it out.

'You've given us salt instead of sugar,' he roared, his face as red as a traffic light.

My reaction was to laugh and put my hand on his shoulder. 'I'm so sorry, sir,' I said. 'It wasn't intentional – but if my mum knew being a cadet was about making the tea, she wouldn't be very happy.'

Thankfully, it made him smile. But it wasn't much better once I joined the force itself.

A female officer's role was to support the work of the male officers who worked over the road.

WPCs (as we were referred to back then) dealt with issues relating mainly to women: missing children, child neglect and abuse cases, and domestic disputes.

At Leicestershire Police, male officers called us 'Peewees'. Derogatory terms such as 'Office Doris' and 'Plonk' (Person with Little or No Knowledge) were used in other police forces.

But I wasn't deterred: at 22, I became the youngest policewoman ever to be promoted from the beat to sergeant in the Leicester and Rutland Constabulary. After two years, I applied to the CID.

In the 1970s, the CID had its own way of welcoming a woman detective to its ranks – an initiation ceremony called 'station stamping' that was neither pleasant, nor remotely welcoming.

Mine happened as I was booking off duty in the admin office at 11 o'clock at night.

Two officers grabbed me by my arms while a third put his hands up my skirt, pulled down my pants and stamped my bottom with the CID ink stamp – all as four or five other men from the team looked on.

There was little point fighting them off. I knew it was going to happen, however much I resisted.

It was utterly humiliating, just as I suspected this ritual – meted out only to women – was meant to be.

But I focused on the privilege of being a detective. My arrest rates were good – but there seemed to be resistance to me as a female of more senior rank.

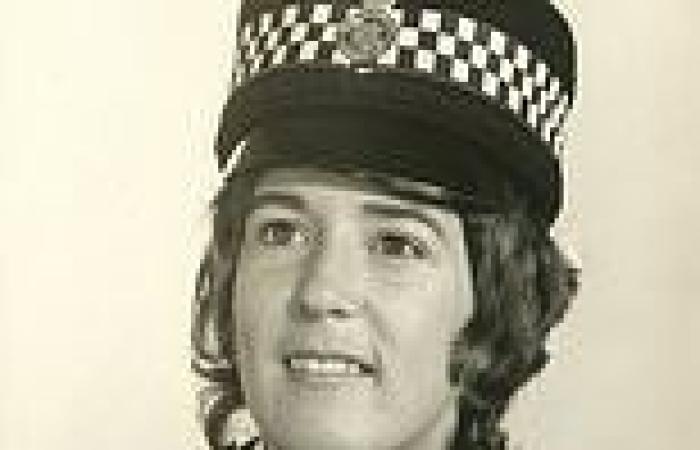

Jackie Malton (pictured) in uniform who was assigned to Scotland Yard's flying squad

This was confirmed during a meeting with Chief Superintendent Michael Hirst to discuss my future.

I'd passed my inspector's exam in 1977, and had been wondering whether there was more scope to advance my career in a bigger organisation, such as London's Metropolitan Police.

His response was far from encouraging. 'If I were you, Jackie, I would go. They don't know what to do with you [here].'

Crestfallen, I asked him what he meant. 'The men aren't used to reporting to a woman, and it makes them feel uncomfortable,' the Chief Super said. 'I know it's not fair, but it's the way it is.'

My face was burning with hurt, disappointment and bewilderment. But it gave me the kick I needed.

I'd been in the Met 18 months when I joined the CID. I was later assigned to Scotland Yard's Flying Squad, the mobile unit of elite officers who focus on violent crime and robberies.

It was my dream job. I'd been an avid viewer of The Sweeney, starring John Thaw and Dennis Waterman.

The fictional squad dripped with machismo – and the reality wasn't too different.

I was greeted on my first day by Detective Inspector Stan Finch, a handsome man with a snappy dress sense: smart suit, coloured shirt with a white collar, and black patent shoes.

He arranged for me to meet my new partner at the Prince of Orange pub across the road from the station at 12 noon.

At about 12.15pm, in walked a strapping man of about 6ft 3in, slightly hunched with a John Wayne pose, a bent nose and a sullen look on his face.

He gave the appearance of someone looking for a fight. It turned out that he was.

DI Finch