Friday 23 September 2022 10:11 PM COSMO LANDESMAN: Three words shattered my existence... Jack is dead trends now

It's said that the death of a child is every parent’s worst nightmare. It is, but there is one big and obvious difference between nightmares and the loss of a child. You wake up from nightmares. Your child is dead for ever.

I got the news of Jack’s death on June 29, 2015, while I was on a holiday cruise ship somewhere in the Mediterranean. I was writing a travel feature for a Sunday newspaper.

On day one I get a Facebook message from Poria Cyrus, an old friend of Jack’s, wanting my phone number so that ‘we can speak as soon as possible’.

Instantly I know this must be about my 29‑year-old son and I message back: ‘Does Jack need help?’

Poria’s clearly worried. I figure that they’d probably met up and my son had talked about wanting to kill himself and Poria is freaked out.

He probably doesn’t know that Jack’s parents know all about their son’s suicide attempts. But we do. I know them so well I don’t worry about them any more.

Like the boy in the fable who cried wolf too many times, Jack threatened suicide too many times. He talked about it too much. Made jokes about it too much. And so did I.

Reading over Poria’s message I think: screw Jack! He’s not going to mess up my holiday. I badly need this break from my London life and I need a break from Jack and all his problems. And the biggest problem of them all: Jack and me.

Lots of parents have a Jack in their life. He can be any age or sex. But the Jacks of this world are lost, lonely, depressed, often on drugs and off the grid of adulthood.

They are full of hurt and anger and self-hatred. They are impossible to live with and impossible to let go of. And their poor loving parents don’t know what the hell to do about them.

I got the news of Jack’s death on June 29, 2015, while I was on a holiday cruise ship somewhere in the Mediterranean. I was writing a travel feature for a Sunday newspaper. Pictured: Cosmo Landesman and his son Jack

You might have seen my Jack around. He’s that tall young man peering out from his black hoodie — the one with torn jeans, split trainers and stained T-shirt. His face is unshaven, unclean; his skin is blotchy and seeing his long, dirty dreadlocks sends a shiver of yuckiness down your spine.

And you shake your head and think: that’s somebody’s son. That trampy-looking creature who begs for money.

That was my son. That was my Jack.

Or I should say: that’s the Other Jack. The Jack he became in his late teens.

Parents don’t have to like their children, but they’re expected always to love them. Sometimes loving a Jack is hard — and sometimes it’s impossible.

I didn’t tell Jack I was going on holiday because I didn’t want him to ask if he could stay in my flat while I was away. I didn’t want to come home to a messy flat and find Jack wrapped up in his dingy duvet, on the sofa watching YouTube videos.

A kinder me would have said: ‘Hey Jack, I’m away for a bit. Do you want to stay in my flat?’ That simple act of kindness could have saved his life.

Jack had friends in my Islington neighbourhood he could have hung out with, but none where he lived in Harrow in a small rented room paid for by his mum and me.

So while I was on my luxury cruise Jack was probably trapped in his little white cube of a room.

Of course, I can’t be certain that letting Jack stay at my place would have saved his life. But neither can I rule it out.

2022

When I first started writing this book a few years ago I made a solemn vow: no life lessons. No uplifting truths or sound advice for suffering souls.

But here’s what I’ve discovered: there are things worse than appearing soft and sentimental, and there are things even worse than offering life lessons. And the main one is doing nothing.

So here’s my Life Lesson Number One: Be kind. There. I said it. I can’t believe I could write something so banal and trite, but I believe it.

Of course, it’s easy to say ‘be kind’ — but how do you maintain kindness with kids like Jack who drive you crazy? You don’t. You try and be as kind as you can be, one day at a time and one infuriating incident at a time. But you have to accept the fact that there will be days when you think, f*** kindness! I’m fed up with this useless lump of a child!

You will just have to accept there are days when you long to kick them out of the house and kick them out of your heart. It’s OK. Just don’t do it. Be kind instead.

Believe me, in the event of a tragedy you’ll save yourself a lot of regret later on.

2015

I message Poria from the ship and ask if he knows why Jack hasn’t been in contact with me. And Poria messages back: ‘I’d rather speak on the phone.’

Could this be it? That terrible thing I’ve been both dreading and denying would ever happen for the past five years? The last time we spoke — eight days ago — Jack was trying to get a job cleaning windows, and was even asking my friends for references. That isn’t the action of someone planning suicide.

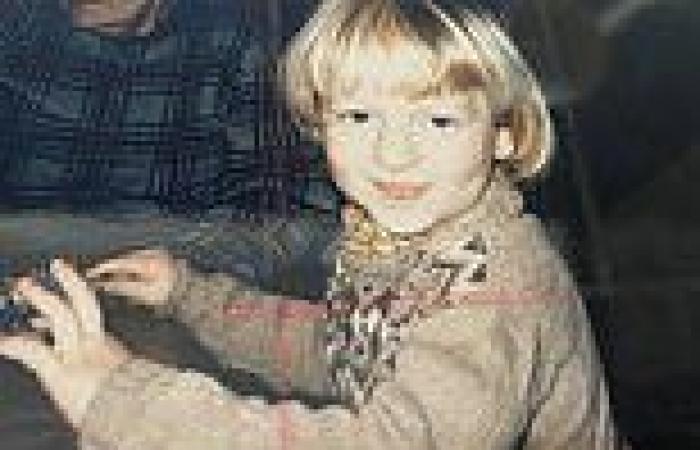

Here’s Life Lesson Number Two: Hug Them. Just hug them. Just keep hugging them and let them know how much you love them. Do it every day. Make them beg for you to stop hugging them, to stop telling them you love them. Pictured: Jack as a boy

And now Tessa, an old girlfriend of mine who had been keeping an eye on Jack, is trying to contact me on Facebook. Now that’s scary. Unable to make contact with her or Poria from the phone in my cabin I go to the ship’s reception desk to see if they can make an emergency call for me.

‘It’s ringing,’ says one of the staff, and hands me the phone.

2010

The first time Jack mentioned suicide was one afternoon in my flat. We were having tea and discussing Jack’s favourite topics: My Sh** Life. My Loneliness. My F****d This and my Unbearable That. And then out it popped: ‘Yesterday I tried to kill myself.’

This was the first time the word suicide came into Jack’s story. It hit me like a surprise slap in the face from a passing stranger.

I knew Jack had, since his teens, suffered from depression and anxiety. His use and abuse of drugs had landed him in an expensive rehab centre after hearing voices telling him he was going to hell.

He’d dropped out of university and then dropped out of life. So I knew my son was a bit screwed up, but I had no idea that he was this screwed up. Till that moment I’d assumed that with the right medication, large doses of therapy, parental support and love — and Jack getting off his lazy arse — he’d be OK.

But Jack’s talk of suicide changes everything. Suddenly I am a dad with a suicidal son. How did this happen? And more importantly, what the hell do I do now?

Call a doctor? An ambulance? His mum, my journalist ex-wife Julie Burchill?

No, says Jack. Don’t tell Mum. (She lives in Brighton with her husband.) He doesn’t want her to worry and says she’s got enough on her plate, what with her husband not being well.

And I think: Oh, as long as we don’t upset Mummy, we can just freak out Daddy with impunity. Thanks, Jack!

I see now that you weren’t being insensitive but kind and protective. You were more concerned with your mum’s feelings and welfare than your own. You were a good boy.

Jack, did I ever tell you that? I probably did and you probably got embarrassed and muttered: yeah, cheers.

And how did I react to Jack’s suicide announcement? I take a deep breath and tell myself to stay calm. I take on the demeanour of the mental health professional. OK Jack, I say, let’s talk about this. And Jack, stretched out on the sofa tells me: ‘I think about suicide all the time now,’ and I sit in my armchair and stroke my chin in a pose of deep thoughtfulness.

I ask questions and probe my patient gently, always