Laura Bennett was working from home one morning in November 2022 when she started to feel slightly off-colour — tired, struggling to concentrate and feeling a bit detached from the world around her.

'I told my husband Matt I was popping upstairs for a few minutes to have a lie down,' says Laura, 47, a marketing manager and mother-of-one from west Sussex.

But when she stopped briefly in the bathroom on the way, Laura's whole body was suddenly gripped by a seizure so violent it sent her crashing to the floor.

'I remember nothing of it but apparently Matt dashed upstairs and got the shock of his life finding me collapsed on the floor,' says Laura.

'I was in the grip of a very severe seizure. I found out later that a bad one is classed as lasting five minutes or so — mine went on for nearly eight.

'Matt rang for an ambulance and managed to protect me from injury by wedging me up against the bath and holding my head in case I hit it on anything.

'When I came around I couldn't speak for the next seven or eight hours, because of the effects of the seizure on my brain. Nothing like this had ever happened before.'

Laura was rushed to hospital and underwent an electroencephalogram — a scan of the brain's electrical activity — to be told she had adult-onset epilepsy and would probably need to take anti-seizure medicines daily for the rest of her life.

A terrifying incident, without doubt. Yet Laura knows she was lucky to be in the relative safety of her own home, with her husband present, when it happened.

But the dangers of a seizure striking out of the blue like this were illustrated all too clearly by the tragic deaths last year of two eight-year-old girls struck by a car when the driver suffered one behind the wheel.

Nuria Sajjad and classmate Selena Lau were killed when a car, driven by 47-year-old mother-of-three Claire Fremantle, ploughed through a fence and collided with them as they sat on the grass during an end-of-school tea party in Wimbledon, south-west London.

Ms Fremantle was initially charged with dangerous driving but was last week cleared after medical checks confirmed she had epilepsy. It was her first seizure and she had no way of knowing she was a risk.

Now on medication to reduce the seizures, she has relinquished her driving licence to the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA).

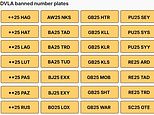

Strict rules mean drivers could face a £1,000 fine if they fail to alert the DVLA when they suffer any kind of seizure or blackout — and not just behind the wheel.

Around one in 100 people — or 630,000 in the UK — have epilepsy. Although it's usually regarded as something that affects teenagers and young adults, around 8,000 middle-aged and elderly adults a year are also diagnosed with it.

It's characterised by bursts of uncontrolled electrical activity in the brain which prevent nerve cells there from signalling to each other properly — triggering seizures where everything from muscle control to senses such as taste and smell go completely haywire for a few minutes.

This leads to seizures, which for some may mean only that their food tastes odd — while others may have such violent reactions that they blackout.

The main treatment is anti-epileptic drugs to reduce seizure risk, by altering the electrical activity in the brain cells so they become less 'excitable' and less likely to misfire. More severe cases may need surgery to remove a small part of the brain that's causing the attacks.

Other approaches include implanting a small electrical device inside the body and wiring it up to the brain to interrupt the chaotic signals between nerve cells, or following a ketogenic diet — low in carbohydrates and high in protein and fat — which is thought to reduce the 'excitability' of nerve cells and can halve the number of episodes.

In children, epilepsy is mostly due to brain abnormalities present from birth.

In many adult cases — like Laura's — it's completely random.

But in older adults, it's often caused by damage to the brain's electrical circuitry from ageing-related health conditions such as a stroke, dementia and brain tumours (the risk of which increases as we grow older).

In fact, Britain's ageing population means epilepsy is now more likely to develop in later years — over 65 — than in infancy.

'The highest incidence of epilepsy is now in the elderly,' says Dr Markus Reuber, a consultant neurologist at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. 'The risks rise with every year of life but are also influenced by conditions seen in older people.'

Unhealthy lifestyles may also put adults at more at risk.

A 2023 study in the journal Sleep found people with sleep apnoea — the snoring-related condition often associated with obesity, in which breathing is constantly interrupted during the night — are three times more at risk of epilepsy than non-snorers.

The theory is that depleted oxygen levels, caused by repeated breathing interruptions, have a damaging effect on the brain's wiring — making epileptic seizures more likely.

Obesity is a major risk factor for sleep apnoea; extra fat around the neck puts pressure on the airways when lying down.

'A seizure can occur with no warning at all,' says Dr Andrew Nicolson, a consultant neurologist and medical director of The Walton Centre, a hospital in Liverpool which specialises in neurological disorders.

'When the electrical signals in the brain go wrong that can happen very quickly.'

Seizures can also be due to a range of factors other than epilepsy — from a rare heart condition called Long QT syndrome (which causes irregular heartbeats that lead to fainting and seizures), to alcohol withdrawal in binge drinkers who have had a heavy session. This is because alcohol suppresses brain cell activity — withdrawal then makes them more susceptible to over-activity, triggering seizures.

One of the things that makes adult-onset epilepsy difficult to diagnose is that many people don't collapse or suffer convulsions — so-called tonic-clonic seizures.

Instead, they have focal seizures which produce subtle effects — a funny taste in the mouth, smelling things that aren't really there, or a very strong sense of déjà vu. In other words, things few people would necessarily connect with a serious neurological condition.

Another sign of a seizure is freezing — coming to a complete standstill for several minutes while remaining aware of what's going on around you , or a 'rising' feeling of fear or excitement in the stomach, as if riding a roller-coaster.

Whereas tonic-clonic attacks tend to involve electrical disruption in several parts of the brain — that then affect several parts of the body — focal seizures often occur in isolated brain regions, so the symptoms are milder and less obvious.

'If a focal seizure occurs in the part of the brain that controls hearing, you may hear noises that aren't real,' says Dr Reuber.

'Or if you are driving and have a focal seizure, you might carry on steering but not be able to turn the next bend properly.

'I've known people with focal seizures to get on trains and travel miles to places they don't even know, or walk considerable distances without knowing why they are going that way.'

Such patients would usually only be diagnosed if and when their condition progresses to a full tonic-clonic seizure.

'Sometimes we see patients with a severe tonic-clonic seizure who have suffered mild events for years with no idea they were a sign of epilepsy,' says Dr Reuber.

This is exactly what happened with Laura. For six months or more before her collapse, she had experienced strange sensations out of the blue — the roller-coaster tummy feeling, strong déjà vu or sudden detachment.

'I could carry on a conversation and didn't lose consciousness, but I'd suddenly feel a surge of fear or glaze over for a minute.

'It only happened two or three times a month; I never thought to bother my GP with it.

'When I told the doctors at hospital about it they said that was all part of the epilepsy.

'My life changed instantly,' says Laura. 'Doctors said I'd be on medication for the rest of my life and for the first year after my seizure I couldn't drive or even take a bath on my own.'

But thanks to a range of different medications, she has not suffered a repeat of that episode and is gradually putting her life back together, working part-time and venturing out more.

She says: 'I'm stuck with epilepsy now — but I'm not going to live the rest of my life being afraid of it.'